In my youth, I emerged from a dysfunctional and alcoholic family unaware of my wounds and deformities. My father had barely spoken to me over my first 18 years of life, and my mother lacked any semblance of boundaries. The result was a young man craving a family and a father.

In my youth, I emerged from a dysfunctional and alcoholic family unaware of my wounds and deformities. My father had barely spoken to me over my first 18 years of life, and my mother lacked any semblance of boundaries. The result was a young man craving a family and a father.

This is why I entered The Church. The strong patriarchy fed my need to be dominated by men as a desperate form of intimacy. The rules helped me to feel contained. The liturgies helped me think I was appeasing an angry God. The clerical clothing, titles, professional ladder, and crosses on chains all boosted a withered self-esteem. And my pledges to fund Mother Church paid for my own abuses.

But as I age and see the church for the sad royal family that it is, I can smell her necrosis even if it remains, for the time being, internal. My father died of necrosis of the inner organs. He looked healthy, but his breath was like that of a slum sewer. He was rotting from the inside out.

And the necrosis can be smelled by younger generations from even longer distances, propelling them from churches like athletes swimming from a sinking cruise liner.

It took hundreds of hours of therapy, 739 books, two bishop’s staff members weaponized against me when I was honest, albeit publicly, about Colorado’s capital campaign, and finally, my one final courageous act – my departure from the church, to learn what three words would be those by which I would begin to live my final phase of my aging life. I would let go of the creeds. I would let go of the long liturgies and their associated kneeling, begging, and shame. I would leave behind the two “great commandments,” the rosary (Greek and Latin), and the hundreds of Jewish rules. Even the Tau Te Ching – read through in only an hour, and still much beloved in my heart would be set aside.

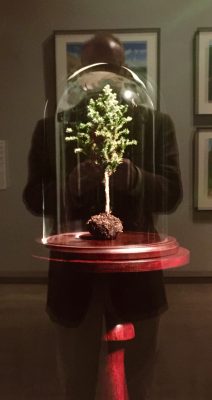

All that remains in the rubble of those desperate rituals and prayers are three roses, climbing up between the broken marble, rebar, stained glass, and cement piles. And if I were the tattooing type, I would ink them on my chest.

Kind. Honest. Curious.

As I age into my final two decades and after almost 60 years of self-searching, I have found my holy grail. It is not a cup. It is three words. I hold up against them what I think, say, and do. Sometimes I fail. Sometimes I am dishonest. Sometimes I am unkind. And occasionally, I lack curiosity. But at least then, I am aware of it and self-correct.

What my time in the “church family” taught me is not dissimilar to that which we learn from the Royal Family of the House of Windsor in England, the Italian Corleone family of the Godfather trilogy, or the Lannister family in Game of Thrones; perhaps it is best to make one’s family rather than stay within the one that birthed you or towards which you crawled seeking to meet, as yet, undiagnosed needs but whose demons feel familiar.

It is true that with age comes the slow deterioration of the body’s strength and beauty as well as the brain’s sharpness. And yet, with aging also comes the dropping of our life-long masks, revealing our true and best selves.

Perhaps they protected us once. Maybe they hid us once. Perhaps they helped us to fit in or camouflage some days. But there comes a time to toss them on the burn-heap, risk the exposure of soft, vulnerable skin and stride out into a new world in which Sundays are for pancakes, beloved honest friends and hikes. Perhaps what is needed now, for some of us, is a season in which what we need is less and less creepy, sanctimonious clergy, reaching through the bars of the golden gages of the massive retirement funds your donations make possible, bestowing blessings on us.

Instead, perhaps we could risk leaving routines that are familiar but not life-giving and so, make room for more silence and for our own heart-mining for the blessings waiting within and around us, all along, in the green and blue cathedral of this planet.

What are your three words? What courage can you muster?